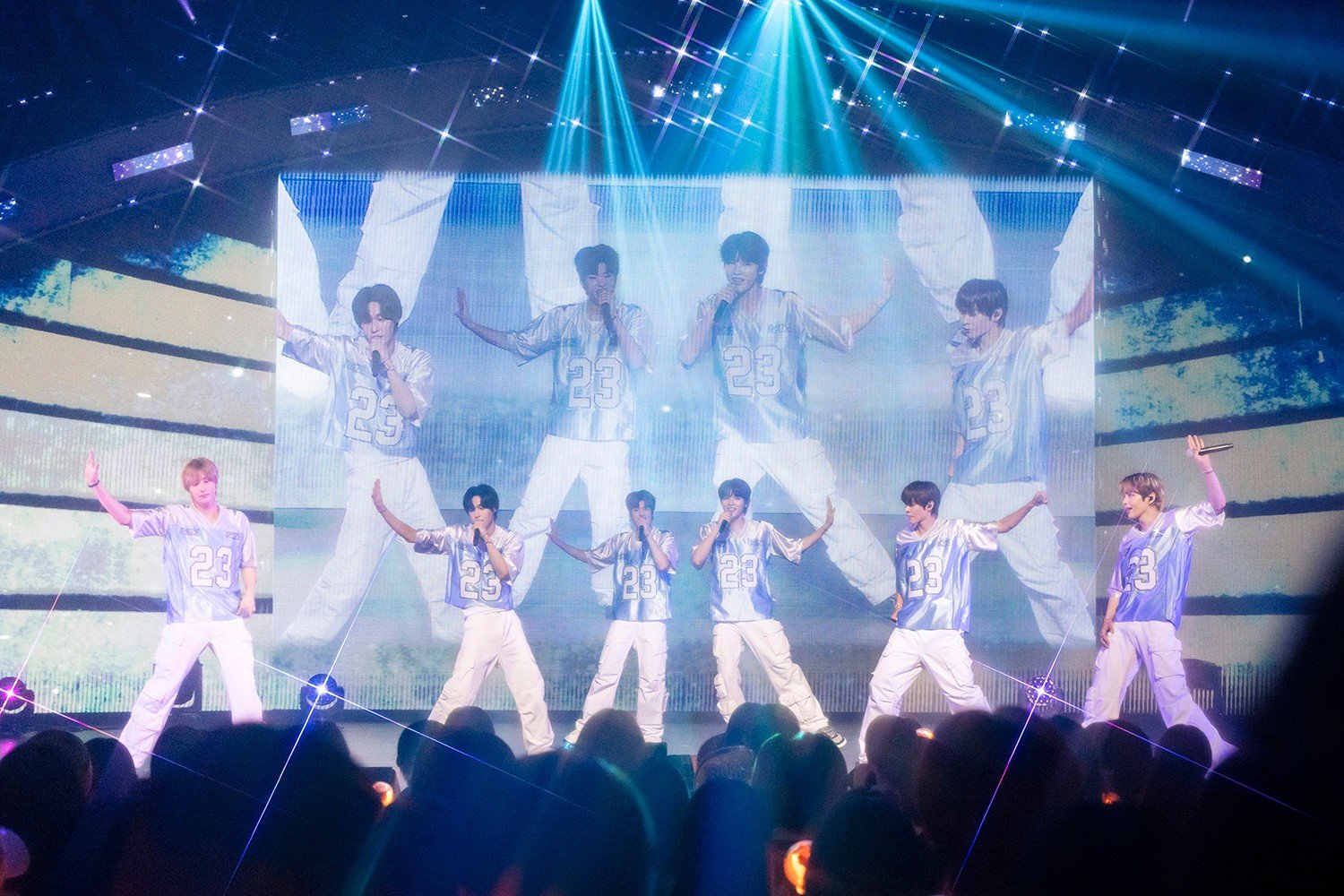

NASA の Advanced Concepts Laboratory によって視覚化された、埃っぽい月の風景。 クレジット: NASA

寒い冬の日、太陽の暖かさは大歓迎です。 しかし、人類がますます多くの温室効果ガスを放出するにつれて、地球の大気はますます多くの太陽エネルギーを閉じ込め、地球を着実に暖めています。 この傾向を逆転させる戦略の 1 つは、太陽光が地球に到達する前に一部を遮断することです。 何十年もの間、科学者たちは、スクリーン、物体、またはほこりの粒子を使用して、地球温暖化の影響を軽減するのに十分な量 (1 ~ 2%) の太陽放射を遮断することを検討してきました。

ユタ大学が主導した研究では、日光を防ぐためにほこりを使用する可能性を探りました. 彼らは、ダスト粒子のさまざまな特性、ダストの量、および影の地球に最適な軌道を分析しました。 著者らは、地球から太陽の「ラグランジアン ポイント」(L1) にある途中のステーションに塵を飛ばす方がより効率的ですが、天文学的なコストと労力が必要になることを発見しました。 別の方法として、ムーンダストを使用することもできます。 著者らは、月からの月の塵の放出は、地球を影にする安価で効果的な方法である可能性があると主張しています。

地球と太陽の間の塵の流れのシミュレートされた放出。 この塵の雲は、地球から太陽の円盤を横切るときに現れます。 月面から放出されたものを含む、このようなストリームは、太陽の一時的な傘として機能する可能性があります. クレジット: Ben Bromley/ユタ大学

天文学者のチームは、彼らの通常の研究の焦点である遠方の星の周りの惑星の形成を研究するために使用される技術を適用しました。 惑星の形成は、主星の周りにリングを形成する宇宙塵を大量に放出する無秩序なプロセスです。 これらのリングは、中心の星からの光を遮断し、地球上で検出できる方法で再放射します。 新しい惑星を形成する星を発見する 1 つの方法は、これらのほこりの多いリングを探すことです。

「それがアイデアの種でした」と、物理学と天文学の教授であり、研究の筆頭著者であるベン・ブロムリーは言いました。

ラグランジュ ポイント 1 のウェイステーションから放出された粉塵のシミュレーション。わかりやすくするために、地面の影は誇張されています。 クレジット: Ben Bromley

天体物理学センターの研究の共著者である Scott Kenyon は次のように述べています。 ハーバードとスミソニアン。

論文は最近ジャーナルに掲載されました PLOS 気候.

キャストシェード

シールドの全体的な有効性は、地球に影を落とす軌道を維持する能力に依存します。 学部生でこの研究の共著者であるサミール・カーンは、軌道が適切な陰影を提供するのに十分な長さの位置に塵を閉じ込めることができるという最初の調査を主導しました。 カーンの研究は、ほこりを好きな場所にとどめておくことの難しさを示しました。

「私たちは太陽系の主要な天体の位置と質量を知っているので、重力の法則を使用して、いくつかの異なる軌道について時間の経過とともに太陽の盾のシミュレートされた位置を追跡することができます」とカーンは言いました.

2 つの有望なシナリオがありました。 最初のシナリオでは、著者は宇宙プラットフォームを L1 ラグランジュ点に配置します。これは、地球と太陽の間で重力が釣り合う最も近い点です。 ラグランジュ ポイントにあるオブジェクトは、2 つの天体の間のパスに沿って留まる傾向があるため、[{” attribute=””>James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is located at L2, a Lagrange point on the opposite side of the Earth.

A simulation of dust launched from the moon’s surface as seen from Earth. Credit: Ben Bromley

In computer simulations, the researchers shot test particles along the L1 orbit, including the position of Earth, the sun, the moon, and other solar system planets, and tracked where the particles scattered. The authors found that when launched precisely, the dust would follow a path between Earth and the sun, effectively creating shade, at least for a while. Unlike the 13,000-pound JWST, the dust was easily blown off course by the solar winds, radiation, and gravity within the solar system. Any L1 platform would need to create an endless supply of new dust batches to blast into orbit every few days after the initial spray dissipates.

“It was rather difficult to get the shield to stay at L1 long enough to cast a meaningful shadow. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, though, since L1 is an unstable equilibrium point. Even the slightest deviation in the sunshield’s orbit can cause it to rapidly drift out of place, so our simulations had to be extremely precise,” Khan said.

In the second scenario, the authors shot lunar dust from the surface of the moon towards the sun. They found that the inherent properties of lunar dust were just right to effectively work as a sun shield. The simulations tested how lunar dust scattered along various courses until they found excellent trajectories aimed toward L1 that served as an effective sun shield. These results are welcome news, because much less energy is needed to launch dust from the moon than from Earth. This is important because the amount of dust in a solar shield is large, comparable to the output of a big mining operation here on Earth. Furthermore, the discovery of the new sun-shielding trajectories means delivering the lunar dust to a separate platform at L1 may not be necessary.

Just a moonshot?

The authors stress that this study only explores the potential impact of this strategy, rather than evaluate whether these scenarios are logistically feasible.

“We aren’t experts in climate change, or the rocket science needed to move mass from one place to the other. We’re just exploring different kinds of dust on a variety of orbits to see how effective this approach might be. We do not want to miss a game changer for such a critical problem,” said Bromley.

One of the biggest logistical challenges—replenishing dust streams every few days—also has an advantage. Eventually, the sun’s radiation disperses the dust particles throughout the solar system; the sun shield is temporary and shield particles do not fall onto Earth. The authors assure that their approach would not create a permanently cold, uninhabitable planet, as in the science fiction story, “Snowpiercer.”

“Our strategy could be an option in addressing climate change,” said Bromley, “if what we need is more time.”

Reference: “Dust as a solar shield” by Benjamin C. Bromley, Sameer H. Khan and Scott J. Kenyon, 8 February 2023, PLOS Climate.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000133

「主催者。ポップカルチャー愛好家。熱心なゾンビ学者。旅行の専門家。フリーランスのウェブの第一人者。」

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25592468/2113290621.jpg)

More Stories

スペースX社がスターシップロケットの打ち上げ準備中、昼夜を問わず火花が散る

二つの大陸で同一の恐竜の足跡を発見

NASAの探査機パーサヴィアランスが火星の火山クレーターの縁に向けて急登を開始